Global ocean temperatures are increasing due to climate change, exposing ecosystems to extreme temperatures called marine heatwaves (MHWs), which can increase the temperature of marine waters by 5°C higher than normal in summer. MHWs can last several months and cause devastating effects on marine organisms.

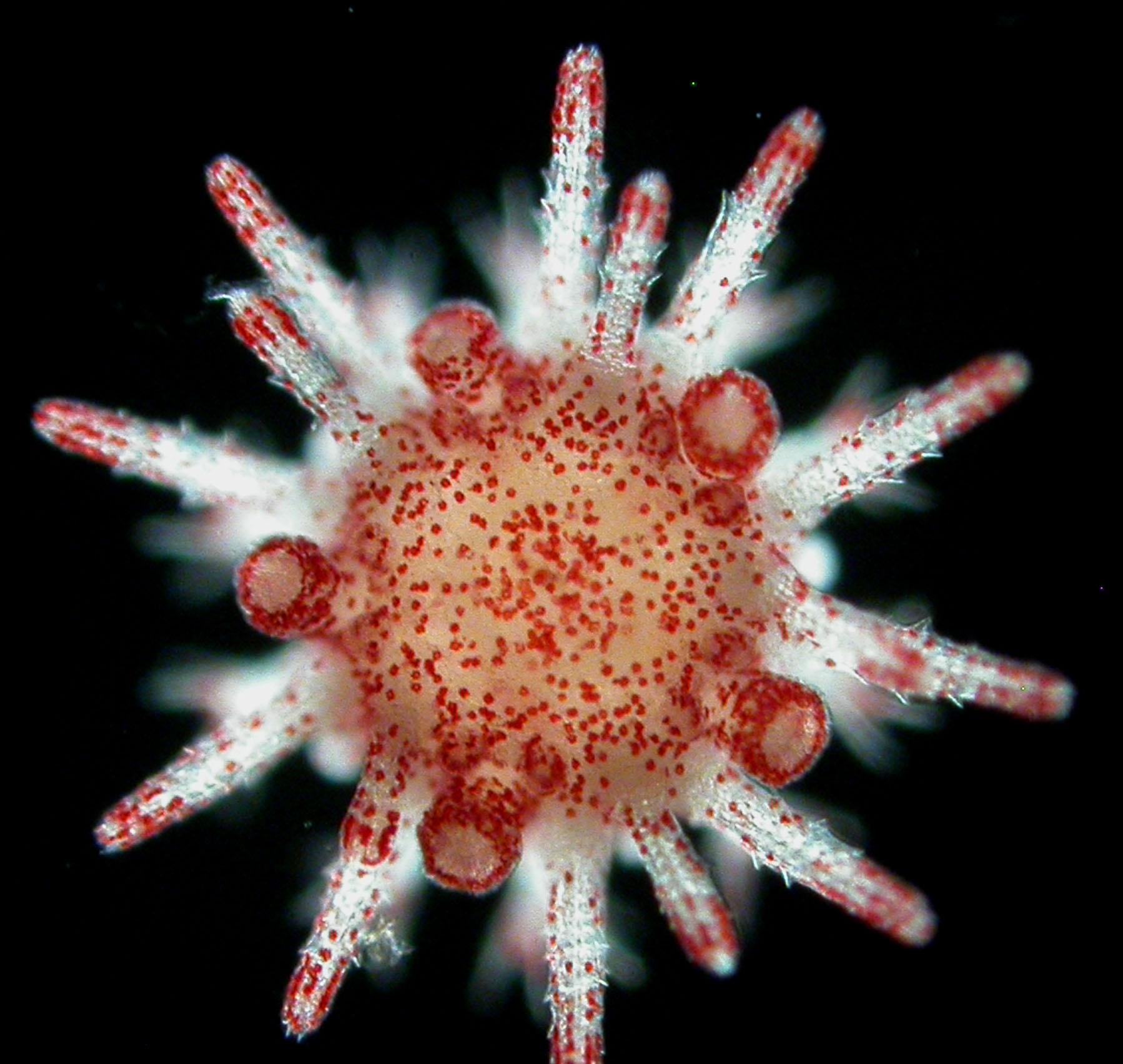

Dr Bayden D. RUSSELL from The Swire Institute of Marine Science (SWIMS) and The School of Biological Sciences (SBS) at The University of Hong Kong (HKU), along with his research group, in collaboration with Dr Maria BYRNE, from the Sydney Institute of Marine Science, The University of Sydney (USyd), experimentally assessed whether adult sea urchins (Heliocidaris erythrogramma) that are exposed to marine heatwaves could pass beneficial protective mechanisms onto their offspring, thus ensuring the survival of the next generation. The findings indicated that adult sea urchins could pass on this heatwave resistance to the next generation. However, the study also identified that these carryover effects may not remain effective throughout the development and growth of juvenile urchins. The findings have been published in Global Change Biology.

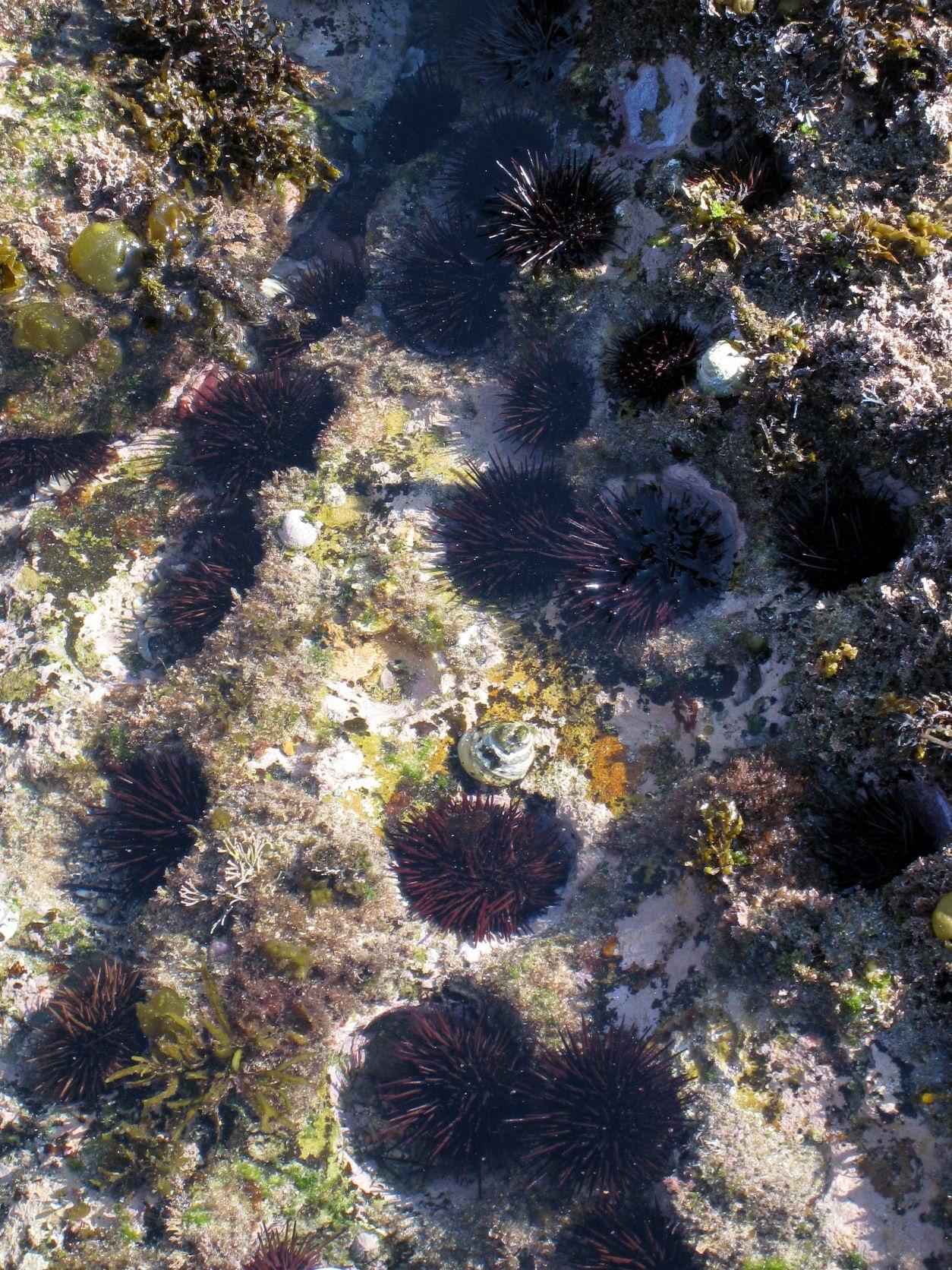

Sea urchins are both economically and ecologically valuable. They maintain the structure and function of benthic marine ecosystems by eating algae that would otherwise take over these systems in the absence of urchins, making the ecosystem simpler and less biodiverse. This role is particularly important in ecosystems stressed by human activities like nutrient pollution or marine heatwaves, which benefit fast-growing algae that replace critical habitats like coral reefs or larger seaweed forests (e.g., kelp forests). Therefore, the continued survival of sea urchins under global heating is key to the continued function of many marine ecosystems.

This current research identified that the ability of urchins to survive extreme conditions through physiological adaptation, and pass on this resistance to the next generation fundamentally depends on their heat tolerance limits. When exposed to thermal stress, some urchin species have the ability to pass on protective mechanisms to their offspring as a means of defence should the offspring come up against the same type of stress as their parents. However, whether these ‘carryover effects’ remain effective throughout the development and growth of juvenile urchins and therefore allow them to survive till adulthood, can vary widely. Importantly, the research identified that different life stages can have very different abilities to cope with thermal stress; so, the responses seen in offspring may be different to that observed in their parents.

The research exposed adult sea urchins to different strengths of marine heatwaves and then spawned the adults under these conditions. The offspring were then reared across a range of temperatures, and their development was tracked to assess for carryover effects from the parents to their offspring. Surprisingly, heatwave-conditioned parents produced faster growing, larger and more heat tolerant offspring. If heatwaves continued, however, there was high mortality in offspring.

"If a MHW occurs at any time during the spawning period of the urchins, these carryover effects could lead to increased survival of the juveniles under what would normally be stressful temperatures. But, if the heatwave continues throughout the larval development, these short-term physiological responses may lead to higher mortality and ultimately reduce the survival of the next generation," said Dr Jay MINUTI, the lead author of the study and postdoctoral researcher at HKU SWIMS & SBS. Therefore, as these types of extreme events become more frequent and intense under climate change, the beneficial carryover effects of parental conditioning to MHWs will only protect the more sensitive juvenile stage and enhance survival if ocean conditions return promptly to normal temperatures.

"These findings are key for our understanding of what some marine ecosystems might look like under climate change," said Dr Bayden Russell. "Sea urchins play a key role in maintaining the function of ecosystems, so if the parents can help their offspring survive the extreme temperatures in marine heatwaves, then this may help overall ecosystem function. Unfortunately, it is clear that the only way to stop heatwaves from becoming worse is to reduce the effects of climate change by reducing carbon emissions. If we don’t, then it is becoming clear that heatwaves will devastate marine ecosystems which are important for human society."

"The species of urchin that we used, Heliocidaris erythrogramma, is native to Australia and is ecologically important in near-shore areas," said Professor Maria Byrne at USyd, who uses Heliocidaris as a model species to investigate climate change impacts. "Its fast development is key to its success in nature, but also provides opportunities for trans-generational research to understand how marine species might adapt to climate change."

With many species of Heliocidaris urchins being ecologically and economically important worldwide (including Hong Kong), this research provides a first key insight into how the next generation could be protected by their parents from the negative effects of extreme temperatures caused by climate change.

The journal paper can be accessed from here: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gcb.16339

Source: https://www.hku.hk/press/press-releases/detail/24883.html